- Viewpoints

Digital transformation (DX) is gathering pace among Japanese companies under the impact of the novel coronavirus. Firms in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector—foods and other daily necessities—are no exception. They have been engaged in a flurry of activity, with impressive results. The industry—including companies that were previously skeptical about whether the digital transformation would deliver clear benefits—is now at major turning point. What does the competitive landscape in the FMCG sector look like today? How can the digital transformation help businesses adapt to it? We asked Shinya Tokuhisa and Masanori Sato of Hakuhodo’s CMP Development Division, who assist corporate clients with DX implementation and digital marketing.

Digital transformation and the changing landscape for FMCG manufacturers

What does “digital transformation” refer to in the first place?

TOKUHISA:

To quote part of the definition given by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, digital transformation means “the use of data and digital technology to overhaul one’s products, services, and business model based on customer needs.” In other words, it means reinventing your business model by leveraging digital. The crux isn’t so much the “use of digital technology” as the “based on customer needs” bit. That’s something people often get wrong.

Mention digital transformation, and harnessing AI and data is usually the first thing that comes to mind. But if that becomes an end in its own right, things are liable to go awry. The way it should work is this: if the customer has a problem, and digital is the most effective way to solve it, then go with digital. Yet too often the opposite happens. You don’t have to use digital if there’s another way to solve the problem. It is true, though, that over the past few years using digital is increasingly becoming the quickest route to a solution. And when it is, it’s time to start contemplating your digital transformation. That’s the order in which things should be done.

What factors lie behind the need for digital transformation in the FMCG sector?

TOKUHISA:

Basically, three tectonic shifts are at play.

First, private-label products have come to occupy more and more shelf space with each passing year. Manufacturers used to compete mainly against each other. But now retailers like supermarkets and drugstores have become manufacturers in their own right, so they’re competitors too. Retailers put considerable effort into selling private labels in a bid to differentiate themselves from the competition and generate higher margins. That’s a growing trend these days.

Second, there are more new players who sell direct to consumer (D2C), without going through retail channels. Products from brands like these often tend to be more expensive than the typical offerings of the big manufacturers. Consumers’ preferences are becoming highly segmented. People are increasingly willing to pay top dollar for things they really like. The upper end of the market is growing. So competition is fierce as these brands struggle with the big manufacturers for a piece of the action.

Third, manufacturers don’t possess final purchase data—a problem that’s plagued FMCG manufacturers for years. They do conduct some direct sales, so they don’t completely lack data, but it’s far from adequate. They therefore face a conundrum. They don’t know exactly what kinds of people buy their products through retail channels.

Besides these three challenges peculiar to the industry, there is a fourth: sluggish spending due to Japan’s dwindling population and the COVID-19 pandemic. More and more FMCG manufacturers are seriously considering making the digital transformation as a way of turning the situation around. They want to put the concept of lifetime value (LTV) into practice. That means engaging directly with the customer and using data to understand who they are. It also means implementing activations that make the customer like the product even more, so they keep buying it.

SATO:

There’s an important assumption to keep in mind here. Many fast-moving consumer goods like foods, beverages, and other daily necessities are low-priced, plus they’re quickly used up. The cost of switching from one brand to another is therefore low. Consumers readily switch brands in the FMCG market. If they make the wrong choice, they can always buy something else. That makes it a challenge to boost customer loyalty. People at manufacturing firms sometimes tell us, “A digital transformation makes sense if you sell pricey durable goods, but it’s surely pointless in the FMCG sector.” They’re concerned that the digital transformation is going to cost more than it’s worth.

But over the past few years, a growing number of FMCG manufacturers have achieved impressive results by going digital. Even though this trend has been accelerated in part by the pandemic, we predict that it will continue over the long term.

If a manufacturer wants purchase data, they could just buy POS data from the retailer. Is POS data inadequate for analytical purposes?

TOKUHISA:

POS data comes in two forms: generic POS data and customer-specific POS data. Generic POS data tells you which products have been sold and in what quantities, but it doesn’t tell you who bought them. So if there’s a heavy user who buys the same product ten times in a month, you can’t do anything to reward them.

Customer-specific POS data, on the other hand, tells you who bought the product and why. But customer-specific POS data is almost always only available from retailers for a price. It would cost a small fortune to buy it from every retailer. Plus, personal information safeguards sometimes make it difficult to acquire.

The key concepts: Becoming a service provider, D2C marketing, and CRM

What forms of digital transformation have FMCG manufacturers undertaken?

SATO:

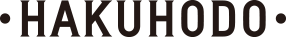

There are three basic approaches corresponding to the three challenges mentioned earlier: transforming yourself into a service provider, D2C marketing, and CRM.

First, transforming yourself into a service provider. This approach can take such forms as a personalized model or a support-program model. The personalized model involves supplying products optimized to the individual customer by using questionnaires and other diagnostic tools to assess their physical condition and lifestyle habits. You can change the combination of supplements they take, for example, or the contents of the product itself.

TOKUHISA:

With the personalized model, first you select the product best for the customer as you serve them. Then you continue optimizing it depending on the results. That way you can rely on the customer to keep on buying it.

SATO:

The support-program model involves continually delivering personalized information and advice to the customer, along with lifelog management functions. That is done using a dedicated app or a messaging app like LINE. Say you sell a health-enhancing beverage. You get anyone who buys it to use the dedicated app. The app keeps a record of their bodyweight, physical activity, and diet. You then provide them with information like what exercises they should do, what foods they should eat, and when’s the best time to drink the beverage. Think of it as selling a health enhancement program rather than a product.

Even if they use the app, isn’t it possible they’ll buy a beverage made by someone else?

SATO:

It’s possible, but there are ways to incentivize them to buy your product. For example, once their record of beverages consumed hits a certain number, you can award them points or give them a reward. The fact is, companies that are quicker off the mark to invest tend to attract more customers.

TOKUHISA:

FMCG manufacturers’ promotional campaigns typically involve airing TV commercials during a particular period as a means of securing retail shelf space and boosting sales. The problem is, sales fall again once the campaign ends. Say you make a product intended to maintain and enhance good health. You’d much prefer it if people bought it regularly throughout the year, rather than just during a particular period. Providing a service that encourages people to get into a routine makes them more likely to stick with your product. That translates into increased sales over the long term.

Whether you adopt the personalized model or the support-program model, transforming yourself into a service provider involves engaging directly with the customer via, say, an app. Digital tools such as apps let you collect data on the customer and thus better understand them. And if a challenge customers face has more than one solution, you can provide each customer with the answer best for them.

What about the second key concept, D2C marketing?

SATO:

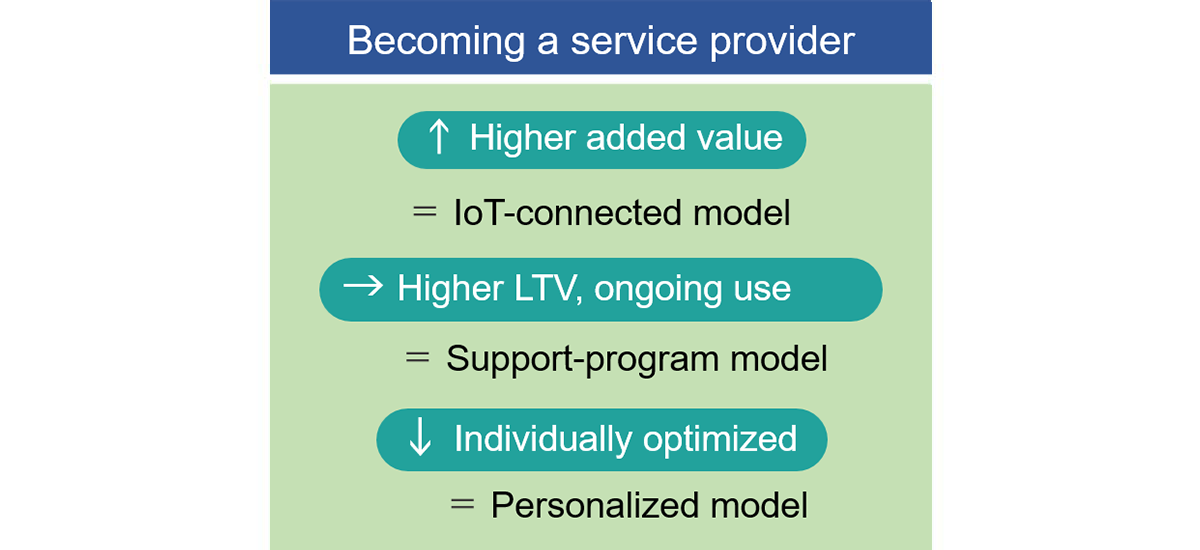

D2C means selling directly to the customer without going through a retailer. It allows the brand to design the entire customer experience, from production to delivery to use. For instance, you can share the brand’s worldview by enclosing a pamphlet or letter explaining the inspiration behind the product. Or you can drive home the product’s benefits by attaching a guidebook. You can also engage with the customer via a messaging app and communicate directly. That gives you access to feedback so you can improve the product or service. And it boosts customer loyalty. Customers who use D2C channels tend to be enamored of the product category or brand in question already. So the idea is to keep them loyal and get them to join you in nurturing your brand.

Big manufacturing firms basically take one of two approaches when they enter the D2C market. They either set up a new D2C operation within the company: the in-house D2C approach. Or they launch a new enterprise in collaboration with another company such as a startup: the spin-off D2C approach. Both approaches involve selling your product without going through retail channels. The key is therefore figuring out how to strike the right balance with retail as you develop your D2C business. You have to be careful not to cannibalize existing sales.

TOKUHISA:

If you conduct direct marketing of exactly the same products as you sell through retail, you’ll end up competing against yourself. To avoid that, you need to be resourceful. For example, when you sell D2C, offer high-end products that aren’t available in regular supermarkets or stores.

The spin-off D2C approach has this advantage: it’s not likely to clash with retail, since you launch a new company and develop a completely new product. It also has another plus. A spinoff is often capable of designing niche products that a big manufacturing firm would find it hard to develop due to small sales volumes. It can more easily come up with products that stand out.

SATO:

But you can’t rely on the brand power of your existing products. And the business tends to operate on a small scale, which makes it difficult to grow sales. It may be of questionable commercial viability in terms of risks and growth potential. It’s important to ask yourself, especially if you’re a big manufacturing company, how are you going to expand business? How are you going to plow the gains back into your other operations? You need to design things accordingly.

Collecting customer data via platform companies

What about the third approach, CRM?

SATO:

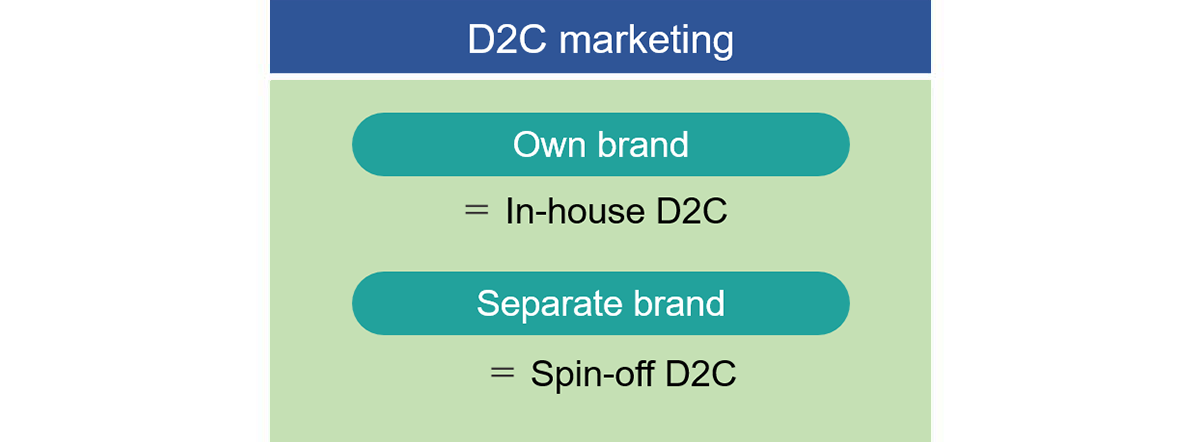

There are three types of CRM as well. First, there’s the owned-channel CRM model, where you use channels you own, like vending machines. Then there’s the platform-assisted CRM model, where you get a major platform company to supply you with data. Halfway between these two lies the intermediate CRM model.

TOKUHISA:

Owned-channel CRM means trying to learn all you can about purchase patterns—via your vending machines, say, if you make beverages. Data from vending machines won’t provide a complete picture, since it excludes retail data. But it’s now sufficient, even on its own, to give you a rough idea of overall trends if vending machines are a significant sales channel.

SATO:

A case in point of the intermediate CRM model is using unique QR codes. A unique QR code is a QR code that differs for each individual item. The QR code is generally printed where it can’t be seen until the item is purchased—on the inside of the package, for instance.

Here’s how unique QR codes are used. First, you prompt the customer to enter some personal information in your dedicated app. Then, when they buy the product, you get them to scan the unique QR code printed on it using the app. Points are awarded for scanning the QR code, so for the customer it’s a similar experience to using a regular loyalty program. Meanwhile, you get access to the customer’s personal data and the product purchase information.

In addition, you ask the customer, via the app, to link their ID with the platform they use (an online shopping site or whatever). If they oblige, their shopping history on the platform (what they bought and when) is linked with their ID on the app. Analyzing the data so obtained doesn’t just tell you about purchase patterns for your own brand. It also tells you about purchase patterns for other brands and in other product categories. It’s even technologically possible to recommend other products you make via the app.

TOKUHISA:

The cost of printing unique QR codes keeps falling, so they’re easier to use than ever. With an intermediate CRM model using unique QR codes, you can create the FMCG equivalent of an airline mileage program. The unique QR code is printed on the product, so you can provide the service to the customer whatever channel they buy it through. It makes no difference whether they get it at the convenience store or online.

With the platform-assisted model, the digital platform develops a suite of CRM solutions based on customer data it’s collected, then supplies it to the manufacturing company. By using the payment data and data on interest in rival brands that platform companies own, you can execute a strategy for nurturing customers into regular, long-term buyers.

SATO:

Platform companies don’t just possess a multitude of customer data. They can also show ads and have their own retail channels. It would cost a fortune to develop all those assets yourself from scratch. For that reason, more and more manufacturing firms these days start with what they can do in partnership with a platform. They don’t try to set up their own CRM program all in one go.

What caveats do you have for FMCG manufacturers implementing digital transformation?

TOKUHISA:

At the risk of repeating myself, don’t forget to ask yourself the obvious question. How can you solve the customer’s challenges? Setting up a digital transformation division, teaming up with a startup, or using the latest digital technology is the means, not the end. Digital transformation is all the rage these days. Mindlessly riding the wave and losing sight of the goal is the most perilous thing you can do.

SATO:

For companies, digital transformation has the advantage of letting them access data by engaging with the customer. But if the customer doesn’t get anything out of it, it’s a one-way street. Then the relationship could end up being short-lived indeed. They might not even show the slightest interest in you. It’s important to devise a mechanism capable of delivering a value proposition and brand experience that keeps people engaged. Make people want to be part of it all. Pique their curiosity. With the old type of marketing campaign, all you had to do was create some passing fun and momentarily capture people’s interest. But if digital transformation is truly to make a difference, it must be designed in a way that keeps people engaged over the long term. And doing that requires a more enduring form of creativity than in the past.

CMP Development Department 1, CMP Development Division

Hakuhodo

Planning Division 1 and CMP Development Division

Hakuhodo